Devoid of meaning

This year’s Meaningful Brand Index research study, from Havas, has succeeded in gaining some frothy headlines. Even the Financial Times took the bait, with its headline “Marketing fails to resonate with shoppers”.

The UK press release about the 50,000-consumer, 14-country study offers contentious titbits to generate more of the same: “Only 5% of UK brands noticeably improve quality of life”; “Most UK consumers would not care if 91% of brands ceased to exist.”

Umair Haque, director of Havas Media Labs, which conducted the survey, claims that the findings should send “big smoke signals to boardrooms.”

He should be more concerned about smoke and mirrors closer to home. This is one of those reports that tells you more about the research industry than the subject it purports to illuminate. Long on rhetoric and short on rigour, it is a classic example of too much extrapolation from too little data.

Where to start? How about at the parochial level, with the report’s ‘Top 10 UK brands’, as measured on the study’s ‘meaningful brand’ metric. Marks & Spencer, Sainsbury’s and Unilever take the top three slots.

There must be at least 10,000 brands for consumers to choose from in the UK. So these are the top 10 from that brand base then? No. They are the top 10 from a preselected list probed by the researchers. How many brands on that list? Just 20.

How were those 20 brands selected? According to a Havas staffer: “They were the ones our senior management came up with.” If you’re wondering why brands such as Apple, Virgin and John Lewis didn’t make the UK top 10, it’s because they were never in the preselected 20.

Later, the report weighs in with the observation that, today, “personal wellbeing is a key driver.” Of what, it doesn’t specify, but my understanding is that it is talking about brand equity. The data appears to reveal nothing of the kind. In fact, the researchers prompted the issue of wellbeing by asking which brands offered it, then found that 95% were falling short.

If people are buying brands despite the fact that they perceive them not to contribute to wellbeing, it is clearly not much of a ‘driver’. Later, the study appears to confirm this, with the finding that, globally, only 35% believed that Coca-Cola enhances quality of life, yet 65% registered a ‘strong personal attachment’ to the brand.

Now we’re getting somewhere, because that discrepancy forces you to look at what people are getting from brands, beyond the product level. A whole body of more rigorous research is out there to tell you what it is: a contribution to personal identity.

For marketers curious about this subtle, pervasive and proven influence on consumption behaviour, I can point you to properly triangulated, well-conceived studies by leading consumer academics of the past 30 years.

They include Belk, with his work on “the extended self”; Fournier, with her input on “brand relationships”; Thompson, with his memorable phrase “project of self”, to which brands contribute; and Ritson and Elliott on “symbolic consumption”.

There are also some illuminating and well-conducted industry studies that intelligently probe the complex relationships between consumers and brands. The Meaningful Brand Index is not among them. I, for one, would not be troubled if it ceased to exist.

Havas isn’t the only one putting forward brand rankings based on its research. Here are some of the other big players…

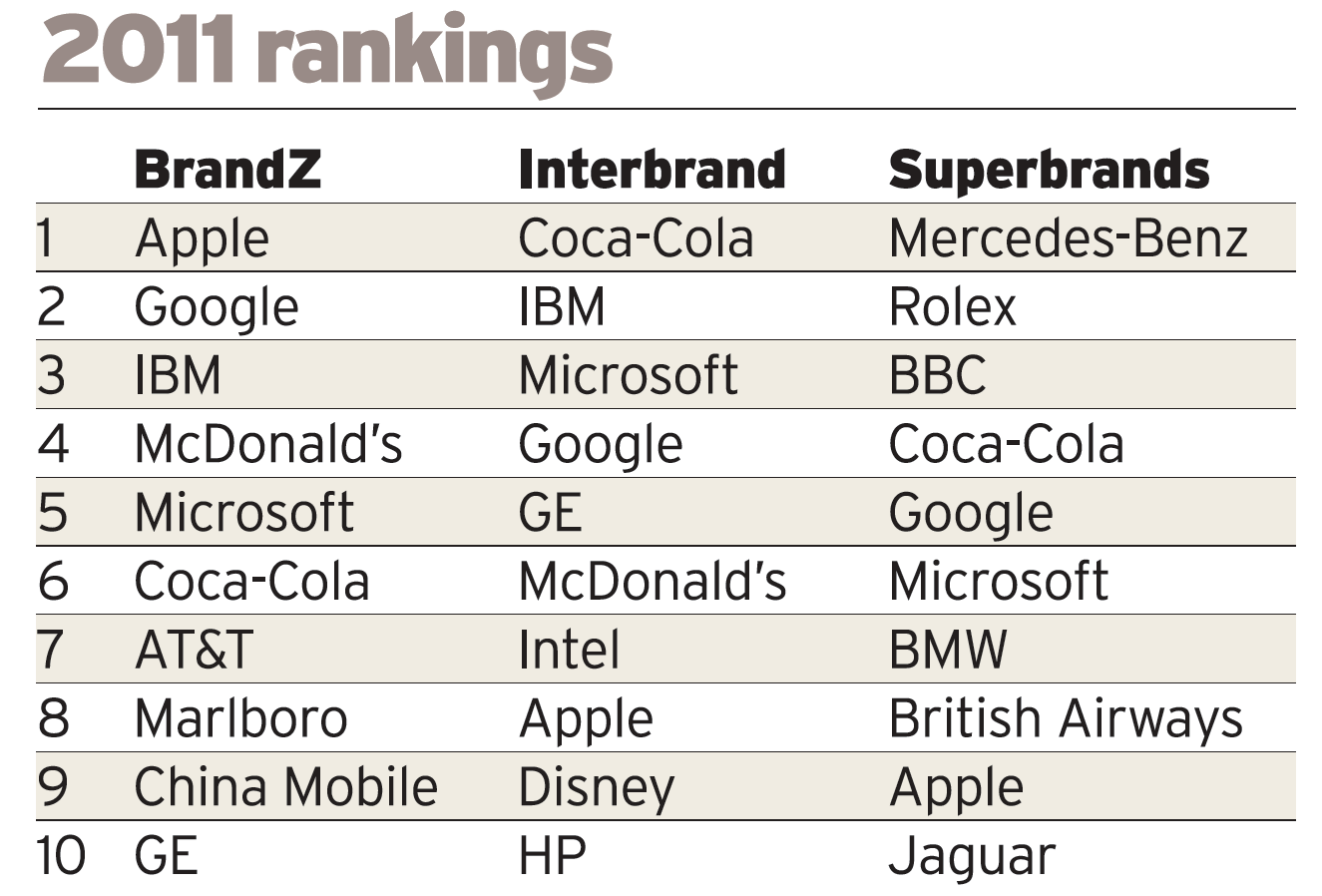

Apple ranked in all three top 10s, but at positions ranging from one to nine.

BrandZ The WPP/Millward Brown monster study is in its 13th year, measuring the value of 23,000 brands across 30 countries.

Interbrand Its Best Global Brands study extrapolates ‘value’ from a series of complex, interlocking metrics.

Superbrands A council of experts ranks preselected brands. The bottom 40% are then dropped and the remaining 60% voted on by members of the public in a YouGov survey. The winners are published in a glossy annual.