Customer service under the microscope

Consumers’ views on the service they receive will make painful reading for some companies

Last year the BBC’s consumer complaints programme Watchdog shone its spotlight on the unloved cable giant NTL. The company had been the subject of a shameful 1,700 complaints, which included one from a woman who had struggled to explain that she would now be handling the unpaid bills of her recently-deceased mother. As requested by NTL, she confirmed all the details in writing, and enclosed a copy of the death certificate. NTL promptly wrote to the deceased mother to say that her permission was required before they would deal with her daughter.

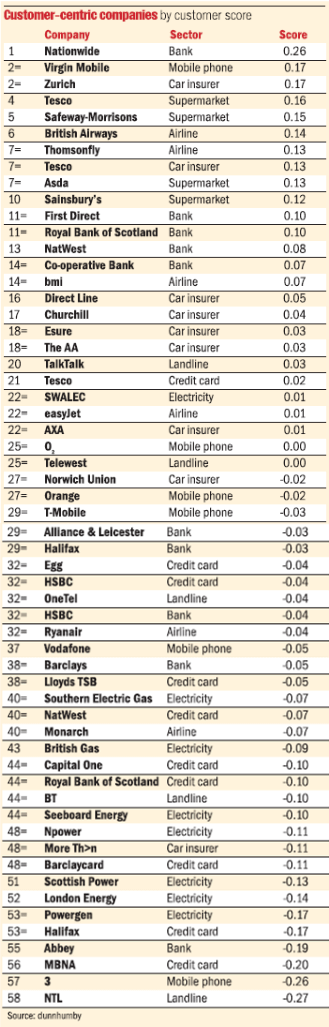

In response to the broadcast, NTL apologised to its long-suffering customers and announced that it had just embarked on a £100 million programme “with the sole aim of improving customer service.” But if it hoped that this would be a quick fix to the problem, it is in for a disappointment. In a report published today, which compares customer ratings of the service of 58 of the UK’s largest companies, it is NTL that sits at the bottom of the list. It seems that money can’t buy customer love – but a glance at the other end of the list gives an indication of what can. In top spot is Nationwide – a brand whose very founding principles go right back to the needs and social wellbeing of its customers. “As a mutual, we have got to be customer-centric,” says Peter Gandolfi, Head of Marketing at Nationwide; “we’re literally owned by our customers.” It is a reminder that good customer service is about deeply-held beliefs, and getting a lot of little things right.

The 58 companies ranked in order of

customer-centricity

The dunnhumby survey is its first on customer-centricity, and its central conclusion is that most of our big companies are getting a lot of things wrong. This quantitative study involved around 1,300 customers rating the service of companies in eight business sectors, from airlines to credit cards. Customers had to have at least six months’ dealings with the companies they rated and were asked to score them on the five factors dunnhumby claim to be the most reliable indicators of customer-centric service (see panels).

Working from this raw data dunnhumby were able to rank the 58 companies, with scores either side of a baseline of zero. Companies were deemed ‘customer-centric’ if their score was in positive territory and ‘customer-distant’ if not. Over half find themselves on the wrong side of the divide. As the report claims, “A significant proportion of companies are failing to fulfil some of the basic tenets of doing business and marketing – identifying what customers actually want and fulfilling those needs.”

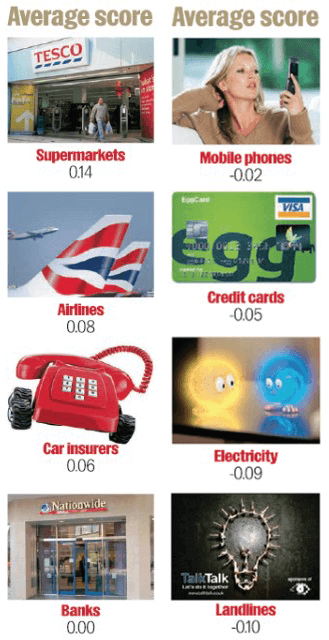

Over-represented in the customer-distant camp are electricity companies, credit card providers and fixed-line telecoms. Supermarkets and airlines, on the other hand, are vastly better at identifying and providing the kind of service people really want. Supermarkets also have the rare knack of improving customers’ service perceptions over time. The difference between these best and worst performing categories is marked, but a simple explanation suggests itself: companies in categories where customers can quickly and easily vote with their feet get better at ensuring customer happiness. Punishment is swift if they don’t. Categories where the relationship is contractual, and escape to a rival brand not without its hassles, have less urgent impetus to be good. The ultimate expression of this principle must be the state-owned, monopoly service and it would be interesting to see how the Post Office would have scored, had it been included.

Some omissions in key categories make the report less authoritative than it might otherwise be: BA tops the airline sector, ahead of Thomsonfly, bmi and easyJet – but would it have done so if Virgin Atlantic had been evaluated? And why no figures for Lloyds TSB Bank or Waitrose in their sectors?

Most open to question though is the title of the report itself. Customer-centricity should be about more inspiring qualities than the basics listed in the five factors consumers were asked to score. ‘Well-trained employees’ and ‘easy to find the right person to speak to’ are strictly hygiene factors – important, to be sure, but a basis from which to build, not the ultimate test of customer-centricity. A business that really put customers at the heart of its offer would find ways to go beyond basic good service to delight and surprise by demonstrating individual care.

Amazon has built its brand this way, pioneering individually-tailored service with its ‘page-you-made’ feature and its personal recommendations based on each customer’s prior searches or purchases. Amazon’s stated vision is to be ‘the earth’s most customer-centric company’ and it is an example of how love-by-algorithm can leave customers with a far greater sense of appreciation than indifferent person-to-person service.

Which sectors did best?

The upmarket travel company, Abercrombie & Kent, is another brand to have seen the value in flattering the individual with personalised extras that go beyond the normal expectations of high quality service. “We try to be creative in how we reward customers,” says Kay Durden, Head of Planning at A&K. This involves the company analysing customer survey data and local-rep feedback to identify customers’ preferences and habits while they were away. A couple who had visibly enjoyed the food of Southern India, for example, might receive a ‘thank-you’ hamper with exotic Indian ingredients and delicacies.

Central to all enhanced service, of course, is good customer data and dunnhumby focuses on this as the vital success factor for its top-scoring companies. Tesco, for example, processes over six billion pieces of data a week, gleaned from its 12 million loyalty-card holders, to help it continually refine its customer engagement strategy.

But dunnhumby’s conclusion from this, that marketing is ‘more of a science than an art’, is to overstate the case for quantitative health. Many companies are very good at collecting mountains of information from customers but bad at doing anything with it. Imagination is part of the game too, and there is an undoubted art to looking at data and reaching for attractive service improvements.

There is an art, too, in crystallising myriad service initiatives into a meaningful brand narrative, or a neat slogan, in order to encourage consumers view them as a coherent whole. ‘Every little helps’ would be risible if Tesco didn’t constantly innovate service improvements – but conversely, those small improvements would be less forceful without the now-famous slogan. Finding ways to brand service excellence, to package it so that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts, is a skill that separates the brilliant from the merely diligent. It might partially explain the high performance of some of the brands on the list. Is Tesco’s Credit Card ranking – easily best of the bunch at No 22 – really down to better service, or is it brand effect, or both?

dunnhumby identified five key factors that consumers consider when they are determining what constitutes good customer service:

They understand and value me

‘They treat me like a valued customer.’ ‘They understand my needs.’

Good staff

‘The employees are well trained.’ ‘Staff tend to be helpful.’

Good customer service

‘The service has become better lately.’ ‘They know what good service is.

Accessibility

‘It’s easy to find the right person to speak to.’

Relevant marketing

‘I receive relevant direct mail and promotions from them.’

Crucially, science will get a company only so far in the key task of motivating staff to provide great service in the first place. A blend of the more intuitive human skills, inspired internal communication and courage are also vital factors in the art of turning employees into passionate service advocates. Virgin Mobile’s strategy, for example, has focused on creating a great place to work, an achievement endorsed by 81% of their staff. Managers are empowered by a scheme called ‘Run Your Own Bit of Virgin Mobile’. And department heads are invited to get a bit of front line action by sitting in on customer calls and serving in the stores. A clearly-articulated vision is also a great way to galvanise a service-based business, and few will be as sweetly framed as Ritz-Carlton’s ‘We are ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.’

For the companies languishing at the bottom of the list, struggling to get the basics right, this is the place to start. Jeremy Davies, Director, Brand Management, at Abbey, talks of “putting in place a vision that will be applied across all facets of the business which will be supported by systems and employees alike.” The result, he claims, will be “an improved experience for all our customers.”

NTL, meanwhile, seems to be pinning its hopes on the chequebook again. It has recently forked out £962 million to buy Virgin Mobile, the second-highest rated company in the report. The deal will make NTL the first to provide the four-way offer of cable TV, internet access, fixed-line telephony and mobile. But as analysts have been swift to observe, it will also bring on board something altogether more important: Virgin’s Midas touch with customers. If Richard Branson can’t rocket NTL up into the top half of next year’s dunnhumby survey, nobody can.