Nowhere to hide

Suppose you are eager to move forward with your career but your plans have been hit by a recent, serious blow to your professional reputation. Nothing illegal, exactly, just spectacular incompetence on your part, mixed with gross lack of judgment. Plus hubris. And arrogance. And sheer bloody-mindedness, if we’re honest.

What are your options here? Do you:

a) Learn from your errors and seek to quietly, but determinedly, rebuild your reputation?

b) Put your ambitions on hold and invest in some capability-development training?

c) Simply change your name?

What a wheeze that last one is! New name, fresh start. All the tarnish and disgrace of the previous one washed away. It’s no longer Roger “rash” McKinley or Sarah “stupid” Jakes; from now it’s, well, anything you like: Zayn Mars? Fergus Forward? Susan Smart? Or maybe something from the ancestral locker to lend a whiff of probity, like Stuart Hanley-Grange or Felicity Cunningham-Phelps.

Any would-be employer impertinent enough to probe back into your previous guise would be brushed aside: that was then, this is now. You’re focused on the future, not the past. You’ve rebranded.

If only rebranding were that easy. As a professional marketer, you are fully aware that it’s not, of course, which is why you’ll do everything to protect your reputation now and repair it should it ever get bruised. The marketers at RBS, conversely, seem to have learned nothing from their recent spell in the stocks.

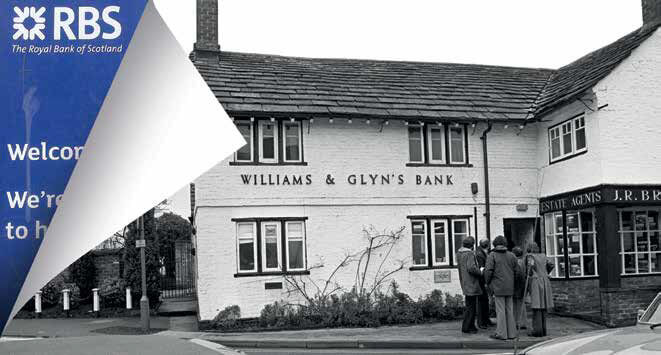

Faced with the continued “toxicity” of the RBS brand, they have reached for the naming placebo. All 300 RBS-branded branches in England will now become Williams & Glyn – a name with whiskers and a waistcoat exhumed from the ancestral vaults.

That isn’t rebranding, it’s delusion. “Hey, with this new-old name, people will forget how we cost the UK economy £20bn and will form a queue to open an account. Foreign investors will look past our incompetence and reach for their acquisition chequebooks.”

No-one’s pretending it isn’t anything but a nightmare for the marketers at RBS, who probably felt they had run out of road. And only a fool would be sure that they were immune to something similar befalling their brand. In fact, that’s really the sobering thought here.

No-one’s pretending it isn’t anything but a nightmare for the marketers at RBS, who probably felt they had run out of road. And only a fool would be sure that they were immune to something similar befalling their brand. In fact, that’s really the sobering thought here.

Accidents happen. Things go wrong. People at the top make hare-brained decisions. Brands get massively damaged. And, yes, when that happens, the answer is to rebrand.

But just as “brand” is 90% substance, so the same principle applies when you put “re-” in front of it. It’s one thing to tinker with the 10% from a position of strength; quite another when the world is baying for your blood.

For what it is worth, here is the path I would counsel in the event of suddenly being thrust in charge of a crisis brand.

1. Do not touch the brand name. The “toxin” will simply be transferred to the new one and the change will give you a false sense that a big step has been taken. It hasn’t.

2. Study the case histories of Perrier, Tylenol and McKinsey, which have all overcome near-terminal brand crises (see panel). It will give you encouragement that it can be done, but will prepare you for just how hard the ride will be.

3. Invest every effort, every pound, renminbi and dollar in meticulous improvement in every aspect of the product-service spectrum: rebranding from the core.

4. When you have proof that customers have welcomed the change, emphasise it with well-judged communications and consider a refreshed visual identity to mark the transition.

5. Set an ambitious but realistic timescale for the full resumption of brand trust: probably in the region of ten to 15 years.

Branding works from the product and service out. Rebranding after a crisis even more so. Whatever the marketers and their advisors at RBS might say, I’ll stake my professional reputation on that.

In 1990, Perrier recalled its entire worldwide inventory –160 million bottles – after harmless levels of the chemical benzene were found in just 13 bottles. Nestlé bought the brand in 1992 and supported it patiently. In 2013, Perrier celebrated its 150th anniversary and today it is available in 140 countries.

In 2011, McKinsey partner Anil Kumar was embroiled in the biggest insider-trading case in the US since the 1980s. Kumar pleaded guilty but the finger was also pointed at two other senior McKinsey employees. The business responded quickly, admitting failure, co-operating with the authorities and tightening procedures. Even then, its global managing director quoted a 20-year perspective for rebuilding the brand’s reputation.

Johnson & Johnson’s painkiller brand Tylenol was hit by a literal life-and death crisis in 1982. Seven people died after taking Extra Strength Tylenol that had been deliberately contaminated with cyanide. Within a week, all 31 million bottles of tablets were recalled and the business invested in the first tamper-resistant gelatin capsules. Back on the shelf ten weeks after the withdrawal, the brand eventually recovered all of its lost market share.